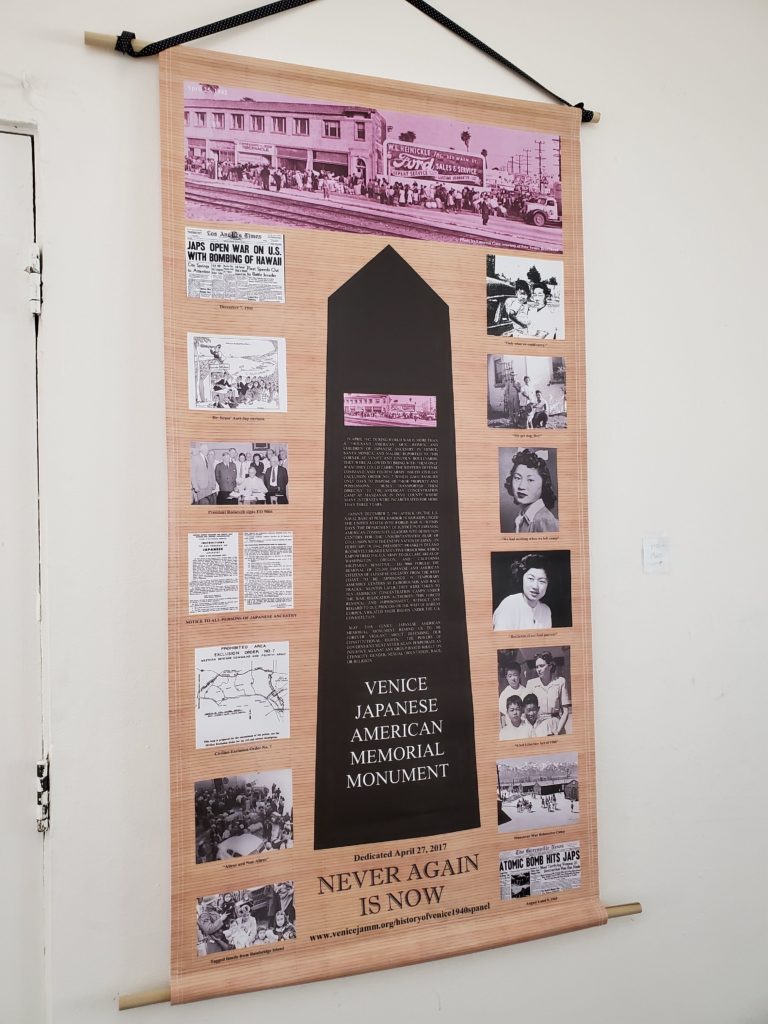

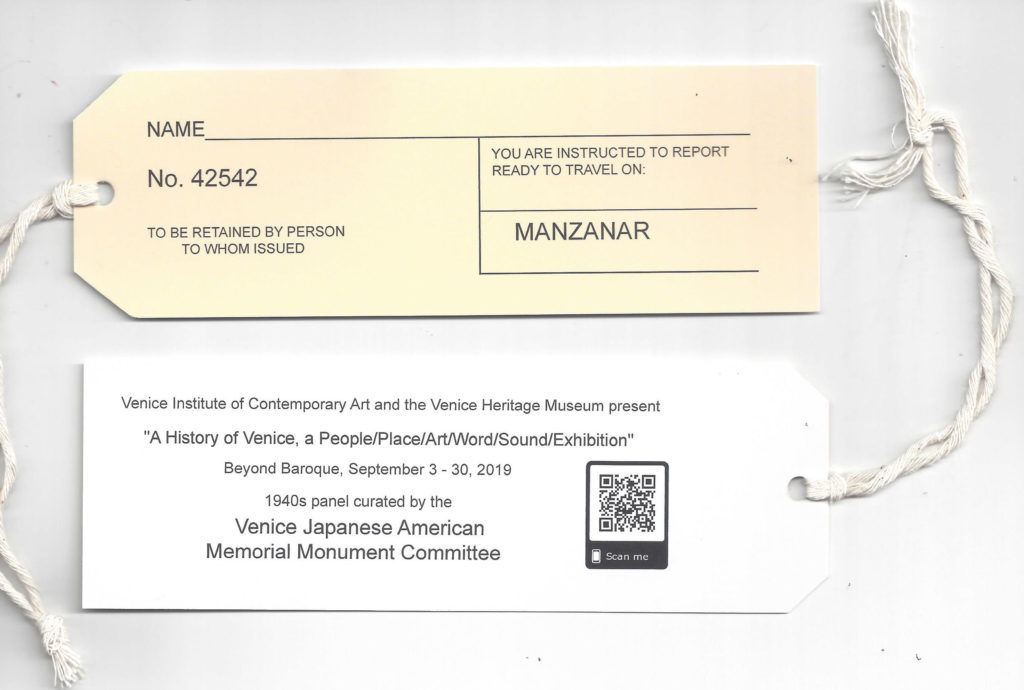

The VJAMM Committee has curated the 1940s panel for “A History of Venice,” a presentation by the Venice Institute of Contemporary Art and the Venice Heritage Museum. This “People/Place/Art/Word/Sound/Exhibition” takes place at Beyond Baroque for the month of September 2019. Here are the elements of the VJAMM panel:

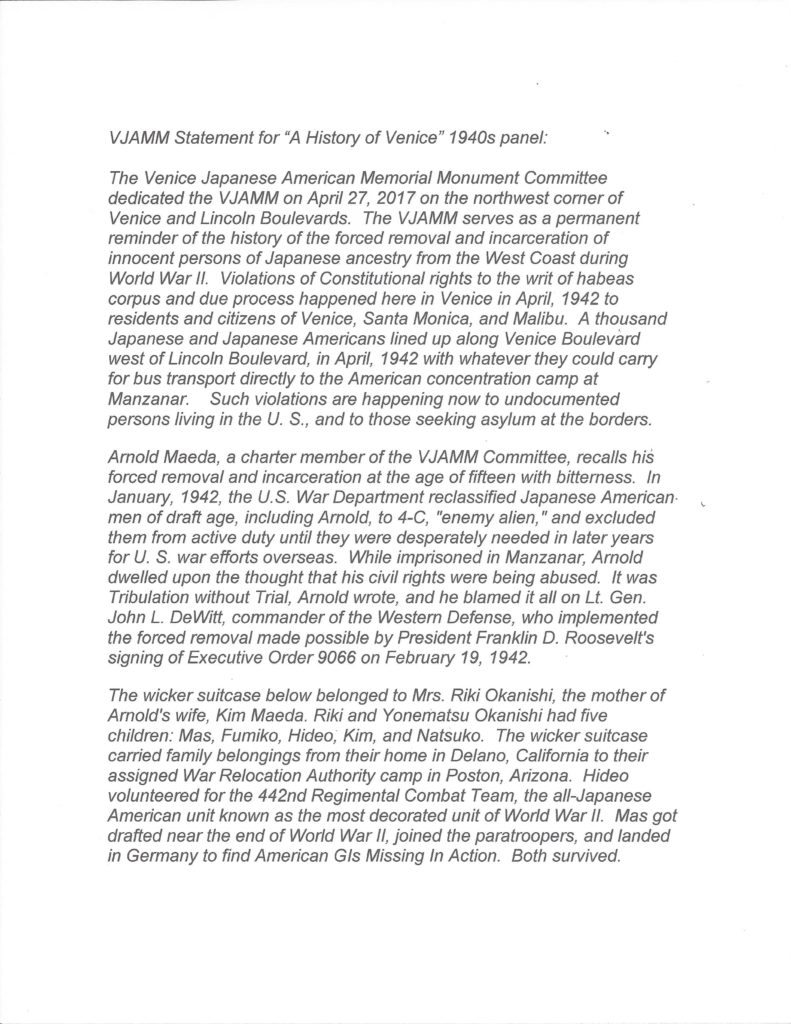

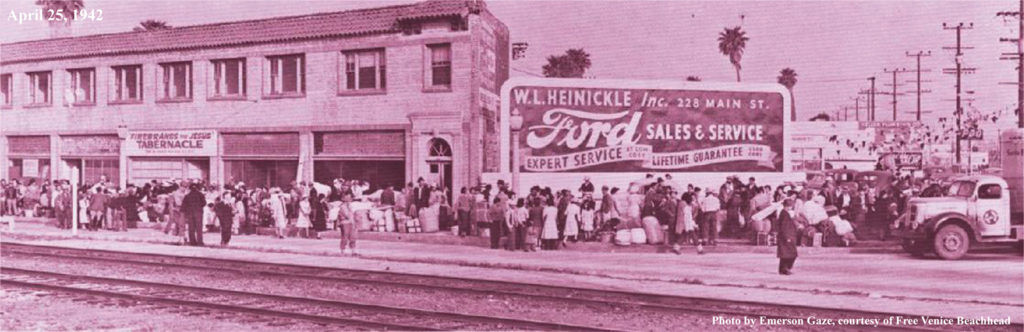

Pink photo of Venice Boulevard just west of Lincoln Boulevard, courtesy of Free Venice Beachhead, and taken by Emerson Gaze on April 25, 1942, depicts persons of Japanese ancestry lining up on Venice Boulevard with whatever they could carry, between the brick building that stands there today and the Red Line railroad tracks that once ran down Venice Boulevard to the beach.

–

–

The Los Angeles Times published this headline the day after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a day, President Roosevelt said in his speech to Congress, “which will live in infamy.”

–

–

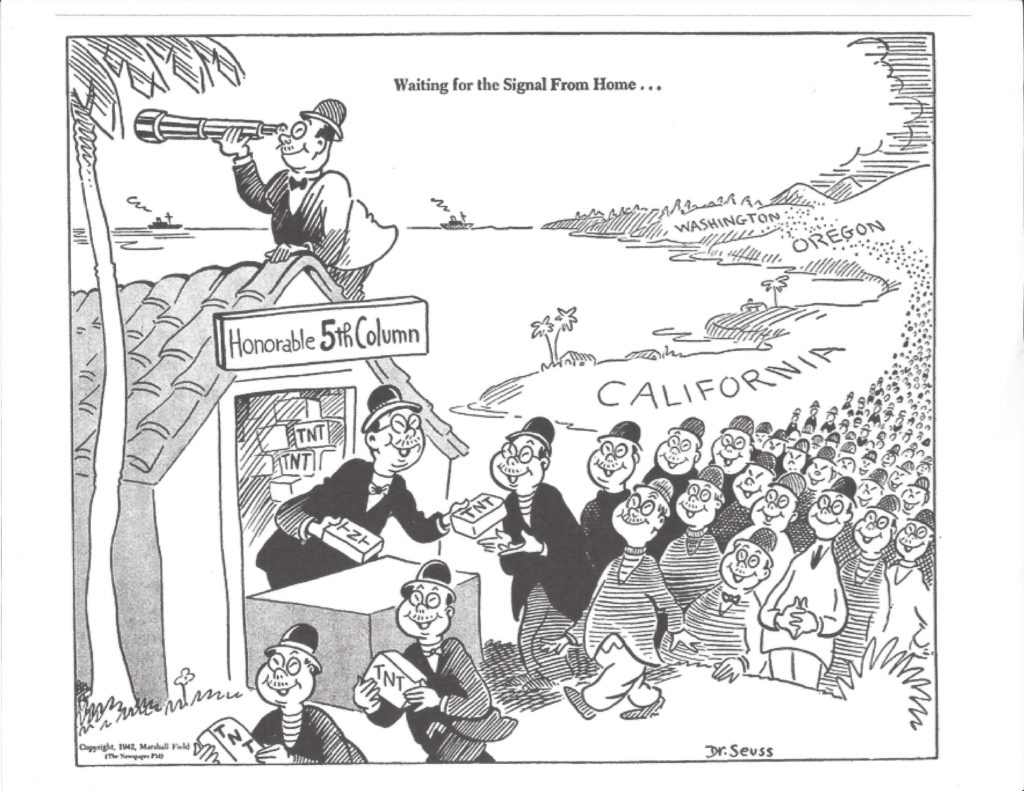

Theodor Seuss Geisel’s 1942 political cartoon depicts Japanese as the Fifth Column of spies and saboteurs in Washington, Oregon, and California. No person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States was ever actually convicted of any act of espionage or sabotage during the war.

–

–

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, as his Cabinet looks on.

–

–

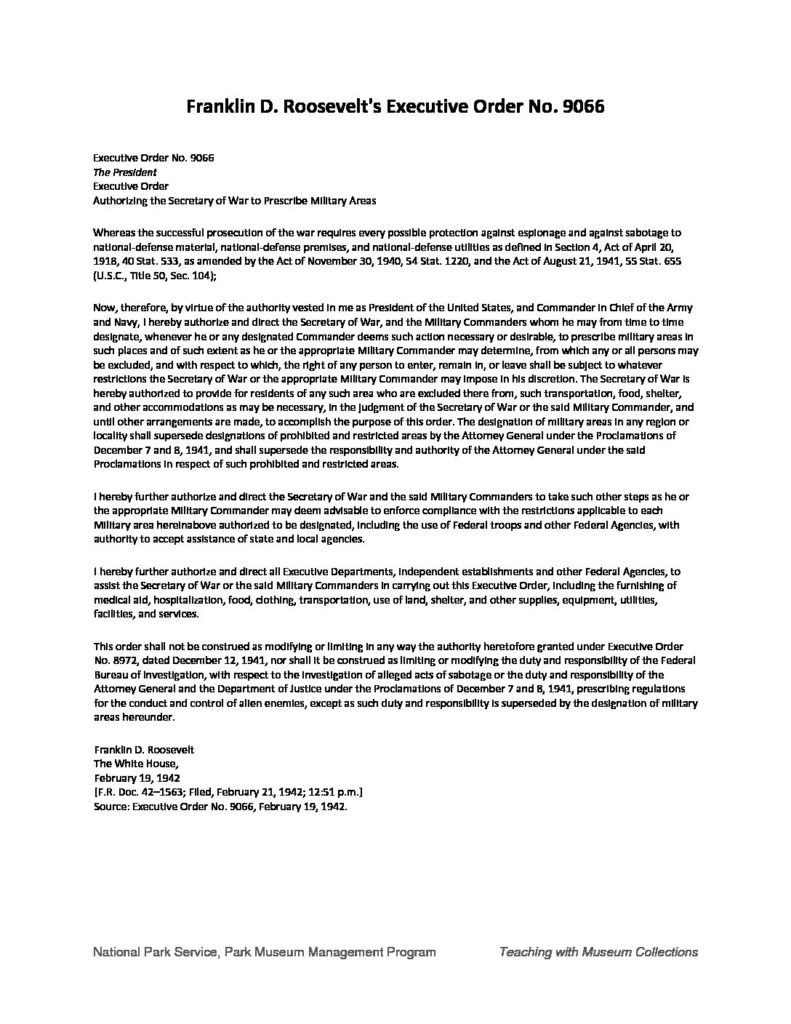

Executive Order 9066 does not specify whom exactly may be removed from militarily sensitive areas in the states of Washington, Oregon, and California.

–

–

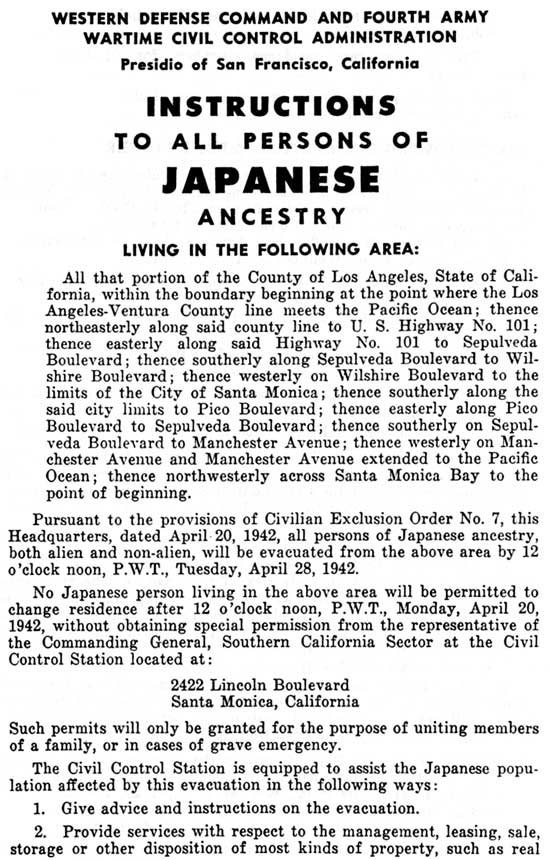

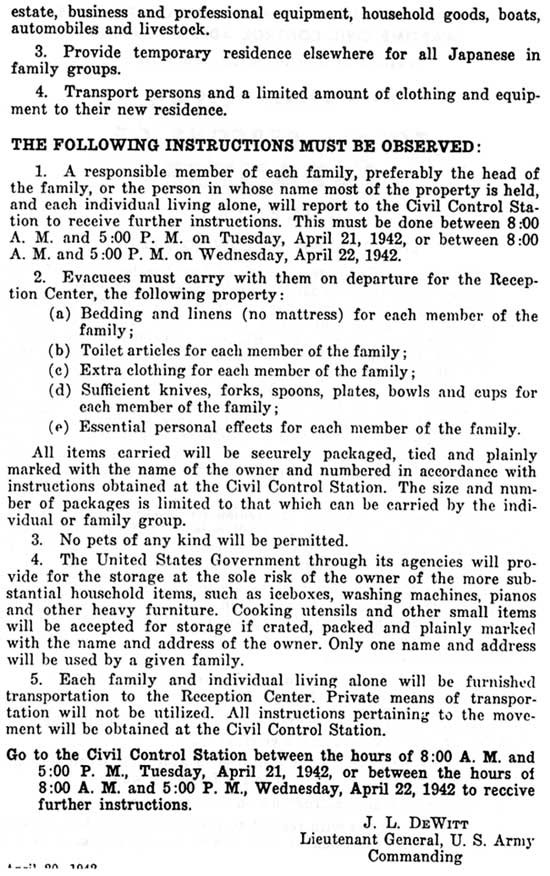

Posted “Instructions to all persons of Japanese ancestry” allowed little time to prepare. Slightly obscured date in lower left corner reads, April 20, 1942.

–

–

Civilian Exclusion Order No. 7 forcibly removed 1,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from Venice, Santa Monica, and Malibu, both “alien and non-alien”.

–

–

Prohibited Area for Exclusion Order No. 7 included Malibu, Santa Monica, and Venice.

–

–

Families packed what they could carry in suitcases and bundles on April 25, 1942, behind the Santa Fe truck parked on Venice Boulevard.

–

–

Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1 forcibly removed 276 Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island to Seattle, to Manzanar, and then to Minidoka, Idaho.

–

–

Arnold Maeda carries brother Brian in this photo taken after World War II.

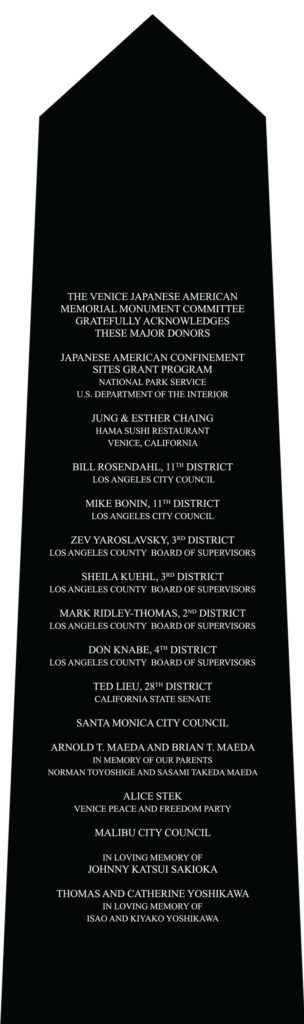

“My family reported to this very corner, before being sent to Manzanar concentration camp with only what they could carry. They, and many other families, lost everything: their homes, their businesses, their liberties.”

-Brian Tadashi Maeda, born in Manzanar

–

–

Toyoshige Norman Maeda, Sasami Maeda, Arnold Maeda, and “Boy,” pose for a photo before their forced removal from Santa Monica.

“Instead of being worried about where we were going, I was obsessed with the fact that I had parted with my constant companion, my pet dog, Boy. For a fifteen-year-old, that was unforgettably traumatic.”

-Arnold Tadao Maeda, from Santa Monica

–

–

Mae Kageyama graduated from Venice High School, Class of 1941.

“When the camp closed, we were given twenty-five dollars and told to leave. But we had nothing when we left camp – no home, no jobs, no prospects. It was very hard on all of us.”

-Mae Kageyama Kakehashi, from Venice

–

–

Amy Takahashi attended Santa Monica High School.

“As a sixteen-year-old, I didn’t realize the injustice fully, but in time we learned how our rights as citizens were ignored. Thanks to the strength and resilience of our Issei parents, we were able to survive.”

-Any Takahashi Ioki

–

–

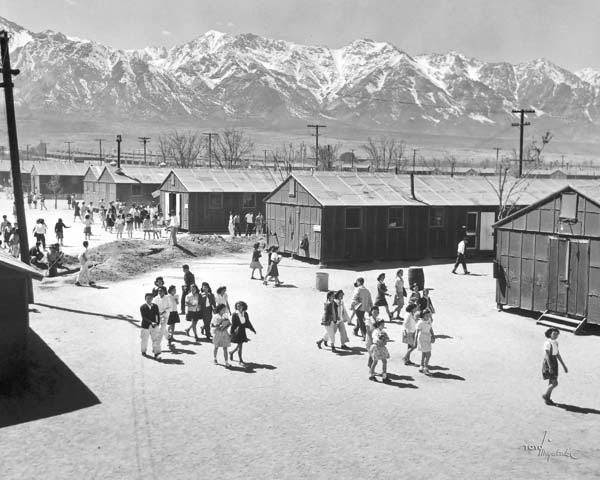

Yoshinori Tomita, lower left, poses with his third grade classmates and teacher, Mrs. Vaughn, at a Manzanar elementary school.

“I was only five years old when we were imprisoned in Manzanar. I feel so grateful to the many Nisei and Sansei who worked successfully for redress and reparations with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. I feel extremely grateful also to all the people in the community who came together to make the VJAMM a reality.

-Yoshinori Tomita, from Venice

–

–

Internee and photographer Toyo Miyatake captured teens walking among some of the Manzanar camp barracks, with the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the background.

–

–

The U. S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, effecting Japan’s surrender.

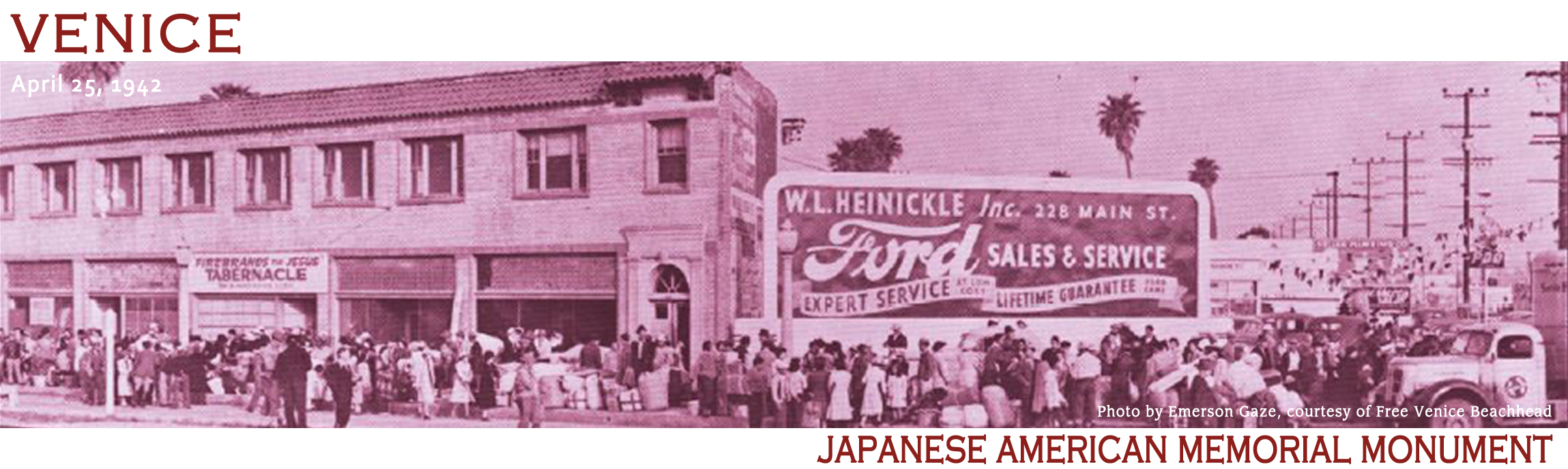

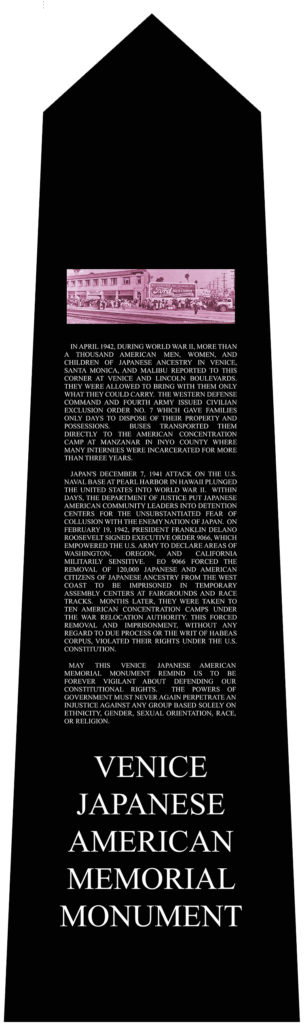

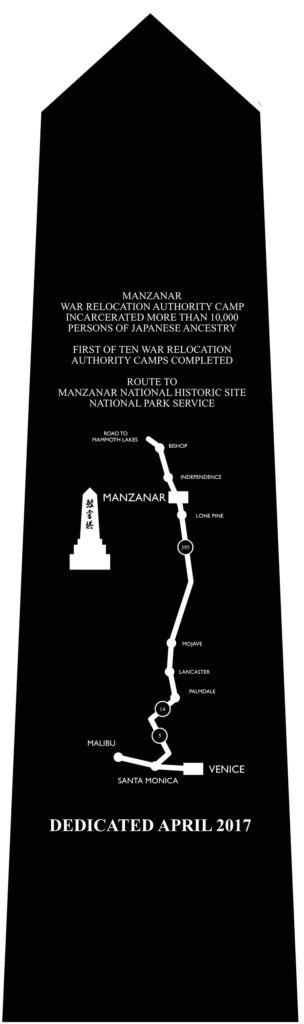

The VJAMM Committee dedicated this monument on April 27, 2017. The VJAMM stands on the northwest corner of Venice and Lincoln Boulevards to mark the spot where 1,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from Venice, Santa Monica, and Malibu reported for transport to Manzanar in April, 1942. The VJAMM also reminds “us to be forever vigilant about defending our Constitutional rights. The powers of government must never again perpetrate an injustice against any group based solely on ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, race, or religion.” For an enlargeable, legible image, please go to < https://venicejamm.org/ >

“NEVER AGAIN IS NOW” because it’s happening again to undocumented workers in the U. S. and to those seeking asylum at the borders: indefinite detention or expulsion without due process.

–